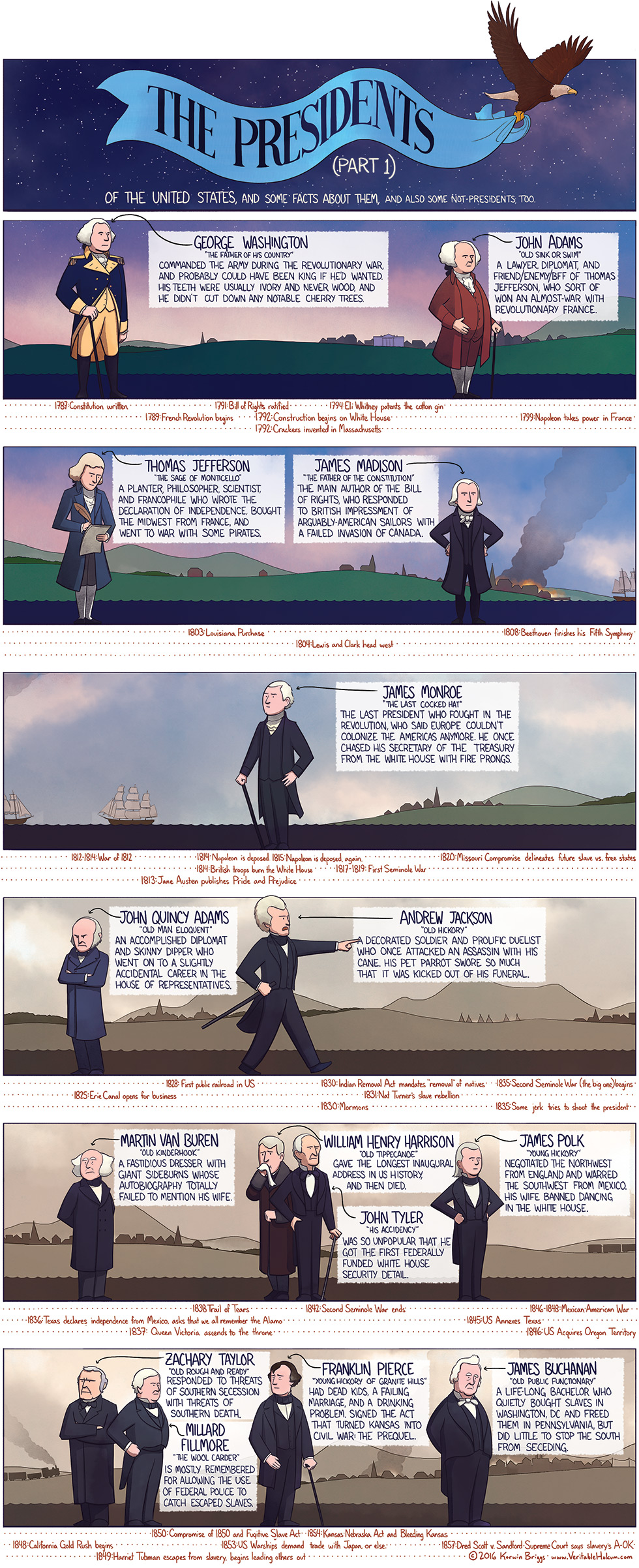

Presidents I: Washington – Buchanan

I may have gotten carried away here. I started with a few funny facts about presidents, and then added some more, and then added some not-funny facts for context, and by the time I realized what I was doing I’d basically covered American History 101. Oops? So I’m going to divide it into a few parts. See also Part II (Lincoln-Wilson) and Part III (Harding-Obama and some others).

George Washington

1789-1797

No Party

Every once in a while I hear folks dismiss the US Founding Fathers as a bunch of old, rich, white men, and in most cases I sort of get where they’re coming from. Like, they’re not wrong, and there’s a lot of awesome non-old/rich/white/male stuff that’s easy to miss if you’re not specifically looking for it. That said, if you want to pooh-pooh George Washington for being old, or rich, or white, or male (and make no mistake – he was all of these), then I’ll pooh-pooh you, because George Washington was downright incredible.

To summarize his pre-Revolution life: he served with distinction in the French and Indian War (which Europeans might know better as Some Unimportant Colonial Bit of the Seven Years’ War), married a rich lady, ran a farm, and gradually became a well-known figure in the resistance to British taxes. When the Revolution started, he was placed in command of the army. From what I’ve read, he did a great job turning a bunch of colonial farmers into an actual military and a not-great job of actually winning battles, but it was enough – America was born! Sort of. It took a few years to decide to write a Consitution, and a few more years to actually agree on one, but in 1789 it was done and Washington was easily elected president.

And this is where I think people miss his importance. He wasn’t just president – he was the *first* president. He had to decide what a president even was. You want to know why I admire Washington so much? He won a war against “George III, By the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, Archtreasurer and Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Brunswick-Luneberg,” and when he had to decide on a title, he went with “Mr. President.” Napoleon Bonaparte and Oliver Cromwell turned their revolutions into dictatorships; Washington navigated his country through its fragile, chaotic first years, and then went back home.

There are also a bunch of weird myths about him, the most popular/false of which are his false teeth (ivory, not wooden, but for sure not comfortable) and his cutting down of a cherry tree and telling the truth about it (totally made up).

John Adams

1797-1801

Federalist

Before the revolution, John Adams was a smart, short-tempered, somewhat-vain Boston lawyer who’d achieved some fame defending British soldiers who stood accused of shooting unarmed civilians in the Boston Massacre of 1770 (they’d for sure fired, but they were also outnumbered and surrounded in the middle of a budding riot). He helped draft the Declaration of Independence, served as a diplomat during the war in France and the Netherlands, was elected Vice President under George Washington, and then won a bitter election against his (former) buddy Thomas Jefferson. But it’s ok – they patched things up later.

Adams’ term coincided with the beginnings of the Napoleonic wars in Europe, and his biggest achievement in office was probably getting France to stop sinking American ships. There’s more to it than that, but if you’re taking a test or something, just mention that he publicized the “X, Y, Z Affair” and you’ll be ok. Probably.

HBO ran a miniseries about him, and while I don’t think Paul Giamatti looks too Adams-y, I’d definitely recommend it.

Thomas Jefferson

1801-1809

Democratic-Republican

Thomas Jefferson was tall, thin, red-headed, socially awkward, and possibly the smartest president the United States has ever had. He studied more or less every scientific discipline of his day, wrote the Declaration of Independence, and invented tons of things including the swivel chair and macaroni and cheese (the dish, not the ingredients). He has a plant named after him. He also (probably) slept with one of his slaves.

He’s the president who made the Louisiana Purchase, which was where the US bought a bunch of nominally-french land in North America. It’s not clear that the sale was totally, 100% legal, but the US wanted land, Napoleon wanted money, Spain didn’t care, and it’s not like anyone was asking the folks who lived there what they thought.

Not related, but still kind of cool: Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died within hours of each other, 50 years to the day after signing the Declaration of Independence.

James Madison

1809-1817

Democratic-Republican

You know the Bill of Rights? For those who don’t, it’s what we call the first ten amendments to the American Constitution, which include things like freedom of speech and religion, the right to a fair trial, and the right to bear arms. When folks say the US is a free country, they’re usually (sort of) referring to this. Before he was president, James Madison was the main author of the Bill of Rights.

He also presided over the War of 1812, which was a very dumb war. See, the British were fighting Napoleon, and needed more sailors, and figured Americans were *basically* British, so they started capturing them on sea and forcing them to work on their warships. The US declared war, except it didn’t have an army, per se, and half the country was against it, and the Americans’ biggest victory in battle took place three weeks after the war ended. At one point the British burned the White House. Now we sing about it before sports games.

James Monroe

1817-1825

Democratic-Republican

James Monroe is best known for the Monroe Doctrine, which is one of those things that most Americans sort of vaguely remember from history class but don’t *really* know what it is. So here’s what it is:

In the early 1800’s, Colonies in South America started winning wars of independence, and people in the United States started worrying that various European countries would help Spain reconquer them. The Monroe Doctrine is what we call James Monroe’s (and subsequent presidents’) policy of stopping that, by force if necessary. The US didn’t actually have much of an Army or Navy at the time, but, you know, it’s the thought that counts.

I don’t know why he chased his Secretary of the Treasury out of the white house, but I saw it mentioned a couple times and figure I would too.

Oh – and he also enacted the Missouri Compromise, which said, basically, that new southern states would have slaves, and new northern ones wouldn’t, and whenever they admitted a free state they’d also admit a slave state so no one felt left out. I actually didn’t get why this mattered until a few years after high school, but I think it’s important, so:

Aside: Why People Cared About Whether New States Would Have Slaves

It wasn’t just a moral thing, or a pride thing, or an economic thing, although those were definitely present. It was about politics, and specifically about control of congress. See, the US has two legislative bodies, the House and the Senate, and every time a territory became a state, it was entitled to representation in each. And the southern, slave-holding states *really* didn’t want to lose their majorities, because then the abolitionists might have enough votes to stop them from owning people.

John Quincy Adams

1825-1829

Democratic-Republican (at the time)

John Quincy Adams lost both the popular vote and the electoral college to Andrew Jackson, but because of the arcane way presidential elections worked in the US at the time, he got to be president anyway, for one term, before getting demolished by Jackson four years later. I think it’s kind of a bummer, because aside from the whole not-winning thing he sounds like a pretty qualified dude – he’d been a diplomat, senator, and Secretary of State, and been involved in lots of major US political history. A few years after his presidency, without really meaning to, he got elected to the House of Representatives, where he fought for civil liberties and against slavery until his death.

Oh, and he was John Adams’ son.

Andrew Jackson

1829-1837

Democratic

Remember that big American victory in the War of 1812, three weeks after the war ended? Andrew Jackson was in charge of that. He was a tall, bold, coarse, mostly uneducated man with a short temper, a merciless reputation, a penchant for dueling, and at least a couple bullets in his body. He was generally pro-slavery, and anti-Indian. He also had a famously foul-mouthed parrot.

He dealt with the Nullification Crisis, in which South Carolina claimed it could ignore a federal tariff if it wanted to. A last-minute compromise solved the problem without bloodshed, but it also sort of left the question open until the Civil War, and is the main reason you’ll hear some people today claiming the Civil War was about states’ rights and not, you know, slavery.

People nowadays are pretty anti-Jackson because of the Indian Removal Act, which led to the Indians in the Southeast being removed (read: forced) from their homes to designated areas west of the Mississippi River. It got pretty bad.

Martin Van Buren

1837-1841

Democratic

In my experience, the only reason anyone knows Martin Van Buren’s name today is because of his sideburns. And aside from that, I don’t have much to say about his presidency. There was a recession (big), the Trail of Tears (terrible), and Texas’s war for independence from Mexico (ignored, for the time being), but other than that, not much to speak of. I’ve heard that “OK” comes from his nickname, Old Kinderhook, a reference to his hometown in New York, but I’ve also heard other theories about it so take that one with a grain of salt.

William Henry Harrison

1841-1841

Whig

William Henry Harrison’s inaugural address was nearly two hours long, on a cold and wet day, which might have contributed to his death from pneumonia a month later. Or maybe typhoid fever, if you believe the New York Times. Either way, his death set off a small crisis because the constitution wasn’t totally, 100% clear on whether the vice president would serve the rest of the term, or just until an emergency election could be held, and it wasn’t officially settled until the twenty-fifth amendment in 1967.

John Tyler

1841-1845

Whig, then Independent

John Tyler was the first vice president to become real president, which ticked a lot of folks off. And he decided to be president in his own right, rather than follow the plans and policies of his predecessor, which ticked folks off even more. A lot of this had to do with the National Bank of the United States, which had been established and unestablished and reestablished and reunestablished over the previous half-century, and which William Henry Harrison had promised to re-reestablish, but John Tyler wouldn’t. The upshot of all this was a president so unpopular that he was assigned the first federally funded security detail, you know, just in case.

He also reached an agreement with the UK over where Maine ended and Canada began (the result of the amusingly-named Pork and Beans War and began the process of annexing Texas (although it didn’t actually happen until a few years later)

James Polk

1845-1849

Democratic

James Polk was basically manifest destiny with a mullet. He came in promising to expand the country, and by the end of his four years as president he’d negotiated with the UK for the (now-)American northwest, added Texas in the south, and taken the southwest from Mexico in a war that his enemies accurately denounced as unprovoked aggression.

Zachary Taylor

1849-1850

Whig

I’ve seen Zachary Taylor described as “rumpled” but I didn’t really get it until I looked him up. Seriously, check this guy out. He’s like the lead in some action-survival movie, like, twenty minutes from the end – all mussed hair and heavy brow and strong jaw and five-o-clock shadow and wrinkled-but-well-tailored suit.

He was a famous general whose presidency was dominated by slavery. Or more specifically, by whether the land James Polk took from Mexico would permit slavery. Taylor said, basically, “you figure it out” and encouraged settlers of New Mexico and California to decide the issue for themselves, which pissed off Southerners because they’d probably end up free states and pissed off Congress because it was usually their job to decide things like this. It got to the point where southern leaders were threatening secession, and Zachary Taylor was threatening to personally lead the Union Army against them, but then he got sick and died, and everyone calmed down, sort of, for a while.

Millard Fillmore

1850-1853

Whig

The big thing to know about Millard Fillmore is that he was the one who signed the Compromise Bill of 1850, which was actually five separate bills that did the following: admitted California as a free state, made New Mexico a territory, paid some money to Texas for giving some territory it claimed to New Mexico, abolished slavery in Washington, D.C., and allowed the use of Federal officers to catch fugitive slaves. That last one was really, really unpopular in the North.

Franklin Pierce

1853-1857

Democratic

I honestly feel sorry for Franklin Pierce. Like, he did a terrible job as president, but his life was so miserable that I almost want to give him a pass. His last surviving kid died just before his inauguration, and his wife blamed him and spent his whole term writing letters to her dead kids. Pierce dealt with it by drinking, a lot.

His best-known “accomplishment” was the Kansas-Nebraska act, which allowed Kansas to vote on whether or not it would have slaves. Southerners and northerners rushed to the state to pack the polls, and then they started shooting each other, and then they kept shooting each other more or less until the end of the Civil War. Newspapers called it “Bleeding Kansas.”

Oh, and I have a note here that someone once attacked Franklin Pierce with a hard-boiled egg.

James Buchanan

1857-1861

Democratic

As far as I can tell, James Buchanan was a smart, well-spoken, generally good guy who was just totally out of his depth. If he’d come in twenty years later, we’d probably think of him as unimpressive but fine, but he had the bad luck of arriving at one of the most trying times in the nation’s history, and he failed. When the South seceded from the United States rather than accept the results of the 1860 election, and started seizing federal property, Buchanan argued that while they had no right to do so, he had no right to stop them.

There were rumors that he was gay, spurred on by his being unmarried and spending a whole lot of time with a male friend, but I can’t say if they’re true. If you want to be sad, though, you can read this story of his one-time engagement.

I’ll leave it here for now, because the pictures are all done but I have some more writing to do. Next week: The Presidents, Part II: Lincoln – Wilson, and after that Part III: Harding – Obama.

~Korwin